In our previous blog post, we discussed the different options for programmers to create web scrapers in several programming languages. This approach to web scraping is fine for people with a proficient background in programming. Unfortunately, there are far more people who need to extract data from the web, that don’t have the necessary programming skills.

In our project “Smart Harvesting II”, our use case was metadata collection for (digital) libraries. We found that there are a lot of cases where bibliographic metadata, that librarians wanted to collect and add to their collections, was not available in machine-readable form, e.g. via APIs or data deliveries. In consequence, librarians and curators often resort to either collecting the data manually via copy&paste, or don’t include the data at all. This is where we thought “Smart Harvesting” could fit in - we wanted to find smart ways to collect bibliographic metadata from the web, with semi-automatic means but without the need to program a full-fledged web scraper.

This is where OXPath comes into play.

What is OXPath?

OXPath is both a domain-specific language (DSL) as well as a tool for web scraping. It uses Selenium under the hood for browser automation, and the descriptive OXPath language at the surface to control the browser and the extraction process in a declarative way.

In the following, we will give a quick introduction to the OXPath language as well as the tool. An extensive tutorial on OXPath can be found on arXiv.

The OXPath Language

The name might hint the reader already at the fact that OXPath is based on the very popular XML query language XPath. In fact, it is a mere extension of XPath which adds the following characteristics:

- web page rendering

- actions to interact with the rendered web page

- extraction markers to select data to be extracted, and

- Kleene star to navigate through a set of pages.

In the following step by step example, we will create an OXPath script that extracts from the list of journals listed in dblp the title of the page, as well as for each journal the journal title and URL.

Every OXPath script starts with a doc function call whose parameter is the URL of the web page to render.

Optionally, an additional parameter can be specifiy to instruct the script to wait a specific amount of time before interacting with the page.

This is needed in cases where the loading of all desired content takes up some time.

doc("https://dblp.org/db/journals/", [wait=60])

Following the doc function call, the remaining part of an OXPath script is made up of XPath expressions to navigate the DOM tree, interwoven with extraction markers to extract desired data at specific locations.

An extraction marker looks like this: :<name> or :<name=value-exp>.

The former notation results in an empty node in the output, which might be used as a parent node to group related child nodes.

The latter results in the return value of value-exp being the content of the extracted node.

In this case, value-exp can be a constant, or the return value of an XPath or OXPath function.

OXPath implements standard functions of XPath and adds some additional ones, e.g. to access node content or manipulate strings prior to extraction.

Continuing with our example, after rendering the target web page, we can address the header element of the page and extract the text from within the h1 tag into an extraction node called “title” like this:

doc("https://dblp.org/db/journals/")

//header[@class~="headline"]:<title=string(./h1)>

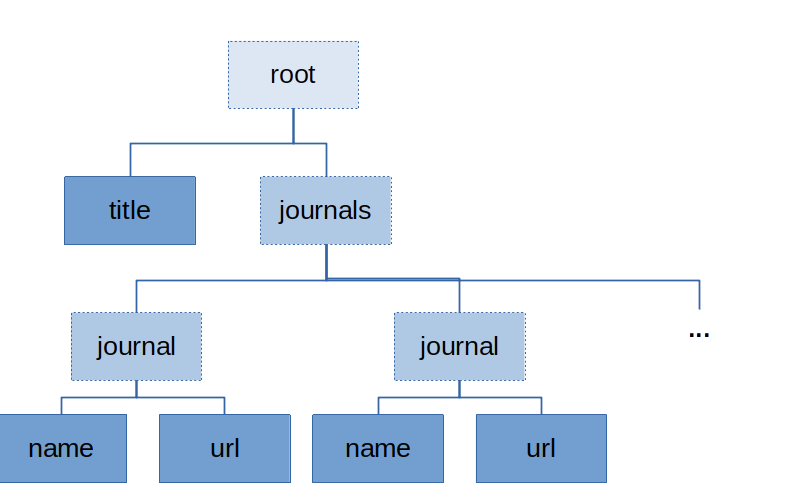

Furthermore, we want to extract a list of journals, and for each journal listed, the journal title and the url. We will need nested output nodes for that to bundle up names and urls belonging together. The envisioned output structure should look like this:

To this end, we insert another extraction marker which is empty, as it will contain child nodes:

doc("https://dblp.org/db/journals/")

//header[@class~="headline"]:<title=string(./h1)>

:<journals>

To create the parent-child relationships, all following expressions will now be an attribute to the journals extraction marker, indicated by []:

doc("https://dblp.org/db/journals/")

//header[@class~="headline"]:<title=string(./h1)>

:<journals>

[

]

Next, we need to navigate the page tree again, to find the titles of individual journals.

Via inspection, we find that the journals are all listed inside a div tag which is a sibling of the header tag that we have addressed so far.

Thus, we need to navigate the tree one up and locate the div tag by its class:

./..//div[@class="hide-body"]

Each individual journal can be found in an a tag, thus we add another empty extraction marker there:

doc("https://dblp.org/db/journals/")

//header[@class~="headline"]:<title=string(./h1)>

:<journals>

[

./..//div[@class="hide-body"]//a:<journal>

]

In fact, this very a tag already contains all desired information - the journal’s name is the tag’s text, the url is found in the href attribute.

Therefore, we can add both extraction markers in one step at the current location, again as attribute to the journal node:

doc("https://dblp.org/db/journals/")

//header[@class~="headline"]:<title=string(./h1)>

:<journals>

[

./..//div[@class="hide-body"]//a:<journal>

[

.:<name=string(.)>

:<url=string(@href)>

]

]

The script so far only extracts journals listed on the given page. The complete list of journals, though, can be accessed by continously clicking on the “next 100 entries” link on top of the list. This is a common case for the application of the Kleene star.

First, we identify the link relative to the extracted title:

./..//div[@id="browse-journals-output"]/p[1]/a[contains(., 'next 100')]

This is the path we need to repeatedly perform the click action upon.

Since we cannot know beforhand, how many clicks we will need to get to the end of the list, we need the unbounded Kleene star (...)*.

We then need another stopping condition. Via inspection, we can see that at the last page, the a tag changes and receives a class attribute of disabled. We employ this knowledge into a combined predicate:

(./..//div[@id="browse-journals-output"]/p[1]/a[contains(., 'next 100') and string(@class) != "disabled"]/{click /})*

Here’s how we include this expression in our script. You can see that this requires only a minor modification, since the path expression following the Kleene star will now no longer relate to the path for the title extraction:

doc("https://dblp.org/db/journals/")

//header[@class~="headline"]:<title=string(./h1)>

:<journals>

/(./..//div[@id="browse-journals-output"]/p[1]/a[contains(., "next 100") and string(@class) != "disabled"]/{click /})*

/.

[

//div[@class="hide-body"]//a:<journal>

[

.:<name=string(.)>

:<url=string(@href)>

]

]

This is what the extracted data looks in XML serialization:

<results>

<title>Computer Science Journals</title>

<journals>

<journal>

<name>3-D Information Modeling; International Journal of ...(IJ3DIM)</name>

<url>http://dblp.dagstuhl.de/db/journals/ij3dim</url>

</journal>

<journal>

<name>4OR: Quarterly Journal of the Belgian, French and Italian Operations Research Societies</name>

<url>http://dblp.dagstuhl.de/db/journals/4or</url>

</journal>

...

<journal>

<name>ZOR - Methods and Models of Operations Research</name>

<url>https://dblp.org/db/journals/mmor/</url>

</journal>

</journals>

</results>

Here’s another OXPath script that allows you to extract all publication from an author’s page in dblp:

doc("https://dblp.org/pers/hd/n/Neumann:Mandy")

//ul[@class="publ-list"]/li[@class~="entry"]

/article[@class="data"]:<record>

[./span[@itemprop="author"]:<author=normalize-space(.)>]

[./span[@itemprop="name"]:<title=normalize-space(.)>]

[?.//span[@itemprop="isPartOf"][1]

:<source=normalize-space(.)>]

[?./span[@itemprop="pagination"]:<pages=normalize-space(.)>]

In this example, you can see the special notation [? ... ] which is used for optional attributes.

This way, attributes can be specified that might be present or not.

As a final example, here is a complete OXPath expression to harvest metadata of working papers from the Bonn International Center for Conversion (BICC) website:

doc("https://www.bicc.de/publications/by-category/all-issues/category/working-paper/")

//div[@class="search-publication-results"]

[./div[@class="search-publication-single"]:<item>

//p/a/{click/}

//div[@class="tx-bicctools-pi3"]

[? ./h1:<title=string(.)>]

[? ./h1:<publisher="bicc - Bonn International Center for Conversion">]

[? ./h1:<doctype="working paper">]

[? ./div[@class="publicationfield cover-field"]/img

:<number=substring-before(substring-after(@title, 'WP_'),'.jpg')>]

[? ./div[@class="publicationfield date_from"]

:<date_from=translate(normalize-space(substring-after(.,'Release date: ')),'-','/')>]

[? ./div[@class="publicationfield abstract-field"]

:<abstract=normalize-space(.)>]

[? ./div[1]/ul/li/a:<url=concat('https://www.bicc.de/', @href)>]

[? ./div[1]/ul/li/a:<lang=string(.)>]

[? ./div[2]/ul/li/a:<author=string(replace(.,'PD Dr. |Prof. |Dr. ',''))>]

[? ./div[3]/ul/li/a:<topic=string(.)>]

[? ./div[4]/ul/li/a:<geoContext=string(.)>]

]

In this script, for each publication item on the result list, a link is clicked that leads to a detail page where all the interesting metadata can be collected. Notice the use of optional attributes to prevent exceptions when some metadata field is missing for an item. Also, this real-world example shows the usage of some of the functions that can be used to normalize or alter data prior to storing it in the output, e.g. normalize-space() for removing spurious white space, or concat() and replace() to concatenate strings and replace specific substrings, respectively.

For a more thorough discussion of the syntax of OXPath and other useful constructs and functions, please refer to the tutorial on arXiv.

The OXPath Tool

OXPath can be used both standalone, or integrated into a bigger application.

For standalone usage, the OXPath CLI (command-line interface) can be run like any standalone Java application:

$ java -jar oxpath-cli.jar

Running the command above in a terminal prints the help information on the tool with all available command line options. The most important option is the path to the OXPath script to be executed. A command might look like this:

$ java -jar oxpath-cli.jar -q path/to/script.oxp

Running this command will execute the script at the provided path, fire up a web browser (the first execution of OXPath will install a specific version of Firefox in the user’s home directory), perform the extraction and print the result in XML format to the console.

Alternate output formats can be specified via command-line options.

Also, the xvfb option (together with the specification of a virtual display) allows Firefox to run in xvfb mode, that is, headless in a virtual frame, thus not visible to the user.

Xvfb must be installed in the system.

OXPath can also be integrated into your Java application, for example. To do this, you first need to add OXPath as a dependency. Then, you can programmatically instantiate the web browser like this:

final WebBrowser browser = new WebBrowserBuilder().build();

With the help of WebBrowserBuilder, the browser can be customized. For example, you might disable Javascript, or specific content types like images.

WebBrowserBuilder browserBuilder = new WebBrowserBuilder();

browserBuilder.getRunConfiguration()

.setDisabledContentTypes(WebBrowser.ContentType.IMAGE)

.setEnablePlugins(false)

.setXvfbMode(true);

final WebBrowser browser = browserBuilder.build();

After setting up the browser,you can fire up the OXPath engine. It will evaluate the given script by running it in the browser, and writes the output to the provided output handler. OXPath comes with a number of output handlers, for example serializing output in XML, JSON or hierarchical CSV format. You can also implement your own custom output handler that fits your use case.

String oxpathScriptString = ...;

final XMLOutputHandler outputHandler = new XMLOutputHandler(true, false, false);

OXPath.ENGINE.evaluate(oxpathScriptString, browser, outputHandler);

String xmlResult = outputHandler.asString();

How is OXPath used in Smart Harvesting II?

Our main motivation for proposing the project “Smart Harvesting” was the fact that bibliographic metadata is not always easy to acquire. Our partner dblp provided us with a very common use case. For them, bibliographic metadata comes from a lot of sources, which include OAI-PMH endpoints, FTP servers or deliveries via email. But there are also some publishers that provide neither form of delivery, such that the only source for bibliographic information are the publishers’ websites.

Prior to “Smart Harvesting”, dblp relied on web scrapers that have been manually programmed in Java and with a lot of regular expressions. But they quickly found that maintaining these wrappers is labour-intensive and time-consuming. Regulae expressions can be extremely fragile, as the slightest change in the web page’s HTML could break the whole scraper. There’s also the drawback that onyl a skilled programmer is able to create new wrappers or update existing ones. To be prepared for the future, we figured it would be better to use some approach that can also be operated and maintained by curators without a strong programming background. Such an approach would then be interesting not only for dblp, but also for other players in the field with similar problems.

To test this approach, dblp has gradually replaced most of their previously Java-based wrappers with OXPath scripts. Using OXPath also has the advantage that it can be seamlessly integrated into the existing Java codebase for the dblp data workflow.

Our other project partner, the GESIS - Leibniz Institute for the Social Sciences, faces similar issues to dblp when collecting new content for their open access repository SSOAR. They also have to resort to manual copy&paste if no API or data delivery from a publisher is available. We decided to provide an OXPath-based module to their Document Deposit Assistant to provide users with the option to harvest bibliographic metadata from e.g. journal websites via OXPath.

Issues

We have to admit that OXPath is not the solution to all web scraping problems out there. First of all, the current version only runs on Linux which might be a major drawback for a lot of potential users. The upcoming version will also support MacOS X, but a support for Windows is only on the far horizon. We tried to mitigate this drawback in the course of our project by providing a Docker container for OXPath that can be run on all operating systems.

Another issue with OXPath is the learning curve, which is steeper than we expected for non-technical people. We still believe that OXPath could be used by non-programmers, but you need to invest some time upfront to really get a feeling for the structure of the language.

Finally, OXPath is currently not open source, which might prevent its application in certain project scopes where the use of open source software is a strong requirement. In today’s times where open science has become a strong movement, we would appreciate a tool like OXPath that is really useful for research projects to also open up.

Conclusions

In this post, we have introduced the web scraping tool and language OXPath. We have introduced the main concepts and structures of the language by giving a step by step example for a script to harvest publication data from dblp.

We have also explained how OXPath has been sucessfully implemented in workflows at dblp and GESIS during the course of the “Smart Harvesting II” project.

In the next post, we will further discuss more options to perform web scraping by the layman.